In 2015 Arnold Schwarzenegger was in a zombie movie called Maggie, directed by Henry Hobson. It isn’t your typical zombie movie and not a typical Schwarzenegger movie either. It’s thoughtful, character driven, dramatic and swaps the usual gore and jump scares to take a much more intimate and personal look at the characters. It’s beautifully shot by Lukas Ettlin with a very naturalistic almost art-house feel to it. I was incredibly fortunate to be able to chat with Hobson recently and ask him some questions about it:

How did you go about choosing your cinematographer Lukas Ettlin? What previous work of Lukas’s did you see that made you want to work with him?

Lukas and I had met socially and I admired his work, Lincoln Lawyer I thought it provided a different take on LA. But it was speaking to him and his shared passion for the aesthetic that we really hit it off.

We went to see Ain’t Them Bodies Saints the week before we arrived in New Orleans and Bradford Young’s spiritual and loving lens bonded us. With Jesse James, you can’t go wrong, showcasing the American west in a poetic way. Never let me go too, Adam Kimmel, who I hugely admire was actually set to come on board for Maggie. But the funding rules meant I had to have a European DP, and so Lukas being Swiss with the same vision won everyone over.

Yep, I storyboarded myself, sadly I left them in the production office which was then cleaned free of any remaining boards…but really they acted as a starting point. With a tricky set of locations, with limited scope we had to rethink our perspective. We scouted the locations a lot, and despite the limitations we found a way of building a natural feel in these disparate places.

Its a bit of a crazy story, as you can tell budget came into things a lot. So when Lukas and I started we found that after the first few days that the 65mm Macro was all we were taking out of the lens box, come day 4 or 5 we noticed that all the other lens boxes had gone… my producer told me that Hollywood Rentals repossessed them…when I found out years later (from Hollywood Rentals themselves) that in fact the producers had sent the others back to save money…but what I love about the lens is that it made everything up close and personal, you delved right into the actors.

A lot of filmmakers talk about limitations making their film better because it pushed them to be more creative. Did you find that with being constrained to the single lens?

I loved it, it really helped build a unique look, I just worked with Matyas Erdely (DP on Son of Saul) and his choice was deliberate to use only the 50mm on that film, our choice was forced upon us but it became a set of limitations that opened up the creativity in unexpected ways.

What camera did you use? Lukas Ettlin has mentioned the Alexa but I also read that it was shot on the Red Epic and Blackmagic cameras as well. Is this accurate? What factors dictated which cameras would be used for which shots?

The Red wasn’t used. Principal photography used the Alexa, but the Blackmagic was used because our limited budget meant we had no time or resources to shoot wide plates. So I went out with a second unit Director during the weekend to get some extra pieces just so we could tell a wider story. The Red might have been behind the scenes, but I cannot recall one on set at all. When Lukas left (he went to shoot Black Sails, this was pre-agreed before we started so no weird politics, he said he could only take the job if he could leave a week early because he had an 8 month offer on the table giving him the chance to direct too, so he helped me find someone to step into his shoes) and Brett Pawluk came on board he was shocked when I told him we only shot with one lens.

This film almost looks like it might have been shot on 16mm. I’m guessing you added grain in post?

Indeed, well spotted, grain was added, the colourist Adam Scott and I felt that the lack of electricity in the world meant it needed a rougher feel, a more naturally worn edge. Film was not a possibility on this, sadly it had not risen again from the ashes at that point, like it has now. And costs were significantly prohibitive.

The footage is softer than you might expect from an Alexa which makes very sharp images. Did you soften the footage in post?

We didn’t, though we didn’t have the budget to shoot RAW so we shot 4444 which might be why. Also there was a lot of post work in the grade. Adam had to do a lot to remove the overtly verdant nature of New Orleans, and that work might have brought down the sharpness. But really it maybe have been the lens, the 65mm Macro was older.

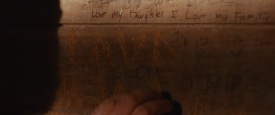

I love working with actors, and Arnold was a true partner, from our first conversation he understood the nature of the roll, he worked hard, harder than most up and coming actors, to showcase his stoic tension. We talked about how Unforgiven changed Clint Eastwood from action star to comedy to drama and this was Arnold’s time. With that he embraced the chance, we stripped back a small amount of carefully curated dialogue that would distract the viewer with his iconic accent (words that make the accent iconic), allowing his natural and often underused performance gift to come across powerfully. A powerful figure, a farmer who spends a lot of time alone, internalizing his thoughts, so when the dialogue did come it was boosted in its poignancy.

Do you have a favorite shot from the film?

I loved one that we got spur of the moment, Arnold against the burning fields. I knew as the grandson of a farmer that farmers would burn their crops to renew, to rebuild once a year. It felt poignant and a powerful message. A failed harvest in a failing world. A moment for him to spend alone… So when we got this stunning sunset we raced, sfx pulled out a burning branch, we walked Arnold through the fields, and then we set fire to a small portion of a field just nearby.

Ironically its probably the shot I like the most, the burning, I wanted to catch the magic hour a bit more, but the rush was not quick enough so it ended up getting darker, which worked even more dramatically.

A tonne, as I mentioned, New Orleans is so lush, so green that for a film that is about the exact opposite, it was a major worry. Adam Scott at the Mill and I worked hard producing a look that would strip away the green, so unlike most features this had to be done shot by shot. (more like a commercial is done)

250, of which I had to do 25 myself… (the budget) but Cinesite were amazing, they are one of the worlds best VFX houses and they went to bat for us. For barely anything.

Yes, the world had to feel constantly imposing, so some worked really well, and are almost invisible, some fought against the natural light which made them harder to believe, but with the unnatural circumstances of the film it made sense.

Don’t be afraid of all the insanity that happens on a film set.

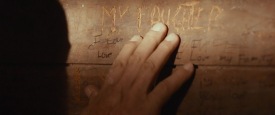

Hobson also gave me some images that did not end up in the final film for one reason or another. I have included them here.

One Response

Very interesting.